As the first country to impose a lockdown in response to Covid-19, China is now one of the furthest down the route to some kind of normality with the resumption of flights. Using data on the Chinese market supplied by Flightradar24, aviation consultancy ICF manager aviation Alastair Blanshard and aviation data scientist Riikka Hasa examine what the new normal might look like.

The future has never been so uncertain, and yet planning for it has rarely been so critical. As the global quarantine is gradually relaxed, passengers will trickle back to airports and aircraft will again fill the skies.

But the flood of government subsidies will also ebb, and many companies are likely to be left behind. The millions of jobs, billions of dollars of assets and years of hard-fought progress that these companies represent will depend on decisions made in the coming weeks.

Having been the initial epicentre of the disease and the first to feel its impact, China is now furthest ahead on the road to recovery and perhaps holds a glimpse of the future for the 2.6 billion people globally who have undergone some form of lockdown. In April, Wuhan finally began to ease its 76-day quarantine. Now as other countries begin to do the same, what can we learn from China’s gradual move to a more normal world?

Using aircraft tracking data from flight tracker Flightradar24, we found two broad phases to the recovery. In the first, essential connectivity was maintained across the domestic network but with fewer than half the number of 2019 flights. In the second phase the number of flights started to increase following the easing of quarantine on 8 April, although with a huge divergence between carriers, notably with LCC Spring Airlines already flying more than 100 per cent of pre-Covid domestic flights. International traffic remains severely suppressed, but government intervention has ensured some level of connectivity is maintained.

Life on the home front

To analyse the domestic traffic, we divided the routes into four categories, using two criteria: short or long and light or heavy. We defined short routes as those below 1,100km, and light flights as those with an average of fewer than 10 daily flights in 2019. Long routes were those above 1,100k and heavy those averaging more than 10 daily flights in 2019. Each route category had an average of 3,000 daily flights in 2019, and as shown in figure one, behaved quite differently.

The weeks following the lockdown in Wuhan were chaos. At the worst point, nearly 900 domestic flights were cancelled daily, representing 75 per cent of capacity and stranding more than 2 million domestic passengers. Many of these were over the denser routes, with shorter routes also slightly worse affected.

In late February, as the quarantine began to take effect and the rate of infection slowed below 1,000 new cases a day from a peak of nearly 4,000, connectivity was tentatively re-established. By early March, nearly three quarters of scheduled routes across China operated some service and President Xi Jinping visited Wuhan to show the worst was past.

But for the aviation industry, this was far from a full recovery. In this phase there was a clear difference between routes, with the longer and lighter routes suffering less and recovering faster.

We suspect this is because connectivity was prioritised over capacity, and once connectivity was re-established over the heavy routes there was insufficient demand to operate additional flights. The shorter routes may also have recovered more slowly as some of the demand could have been substituted by road traffic.

There could also be geographic factors driving this – Wuhan itself is the ninth largest city in China by population and is conveniently located. Many of the shorter, dense routes connecting the heavily inhabited East of China were therefore near the epicentre of the disease, while longer, thinner routes overflying the region or connecting outlying provinces would have been less impacted.

The net result was long, light routes recovering to 60 per cent of prior levels, compared to just 40 per cent for the short, dense routes.

As the Wuhan quarantine was relaxed in April, the domestic market gradually transitioned to the second phase of recovery. figure one shows an inflection as the quarantine was relaxed, with an increasing number of flight operations across all route categories and a somewhat higher rate on the shorter, heavier routes. The average increase since quarantine was lifted is about 12 per cent in a month and helped China overtake the US to become the world’s largest aviation market.

The recovery accelerated leading up to May which continued for the lighter routes but slightly relapsed on heavier routes. In early May the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) was also due to make the delayed transition to summer schedules, potentially leading to further capacity increases.

Recovering services

Different carriers have recovered at noticeably different rates. As shown in figure two, LCCs have recovered to nearly 80 per cent of pre-Covid-19 domestic flight levels, compared to 50 per cent for the full-service carriers. Spring Airlines has recovered particularly aggressively, operating more domestic daily flights in May than in much of 2019.

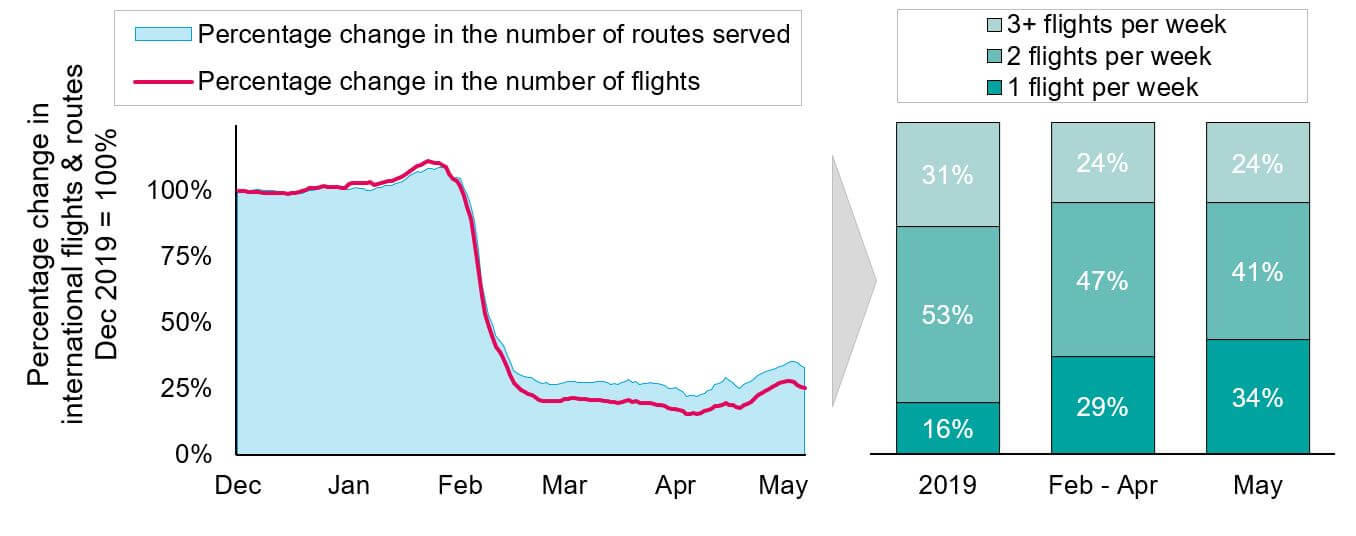

By comparison the international market is on life support. The Chinese government has taken a direct – and restrictive – role in managing routes to foreign countries. From 12 March Chinese airlines have only been allowed to operate a weekly flight to each other country, and each foreign airline was only allowed one weekly route to China. To increase social distancing, load factors are capped at 75 per cent .

At the same time, the government offered airlines subsidies to maintain crucial international connectivity. But set at just $0.003 per available seat kilometres ASK (or 1 cent per ASK if no other airlines serve the route) this only eases the pain. Typical CASKs for long-haul flights are closer to 8-10 cents, so a typical London-Beijing flight would still require an additional $200,000 of revenue just to break even.

As shown in figure three, this may have had a slight impact in mitigating the decrease in international routes served to about 65 per cent in May, while the reduction in flights was about 75 per cent. This can be seen in the breakdown on the right-hand side, with many more routes operating with just a single weekly service compared to 2019 and consequently greater connectivity than the volume of flights would suggest.

These routes will likely have a long, gradual recovery compared to the domestic markets. All indications are for restrictions to remain in place for weeks yet, as politicians avoid the scandal that could potentially result from re-importing infections to fragile populations still feeling the economic and social pain from the first wave.

A phased lifting of these restrictions seems likely, with the EU recently voting to extend restrictions on access for non-EU residents, and discussion of a ‘Trans-Tasman’ aviation bubble connecting Australia and New Zealand as an intermediate step back to open skies.

Encouraging passengers and businesses back to aircraft may take a longer time. The burden of proof for safe operations has always been particularly high for airlines, and airlines and airports will need layered measures to reassure passengers and governments.

Even so, many businesses may be increasingly acclimatised to teleconferencing, and for tourists the thrill of exotic holidays may be overshadowed by an increased sensitivity to the risk of the unknown. Financial pressures are likely to weigh on both.

Positive potential

There is light at the end of the tunnel. Aviation is fundamentally a growth industry and has proved resilient to recessions, oil crisis, terrorist attacks, natural disasters, MERS and SARS.

A survey of aviation industry executives conducted by ICF in April saw 66 per cent expecting the severe reduction in flights to last fewer than four months, and 90 per cent expected traffic to return to pre-Covid-19 levels within two years. In the long term it seems there is little expectation this will dent the global appetite for the opportunities, experiences and benefits created by aviation.

Beneath the surface, the industry that serves this appetite may look a little different though. Each of the previous crises hurt some companies more than others, and this one is likely to be no different. China will have the first-mover advantage, and its large, recuperating domestic network will provide useful feeder traffic when international flights are possible again.

An ability to draw on state aid with fewer conditions has allowed the big three Chinese carriers to avoid mass-layoffs and by mid-March, 77 per cent of major national airport construction projects had been resumed. This will provide them a more solid foundation then many foreign competitors, and is perhaps reflected by the market, with the share price for the Chinese big three recording a trailing 52-week max versus min drop of just 37 per cent, compared to 70 per cent for comparable airlines across Europe and the US. Whatever the outcome, it is certain that many of the seismic shifts to the industry are still ahead of us.

Cargo boost

While passenger flights have been in a downward spiral throughout the pandemic, air cargo carriers have seen an increase in operations. More than 50 per cent of air cargo is typically transported in the belly of passenger aircraft, but with so many passenger aircraft grounded the available capacity has rapidly dropped. Air cargo operators have ramped up to respond to the global and urgent need to deliver medical supplies and to ensure goods are flowing without disruptions.

In March and April, freighter aircraft operated 30 per cent more freight tonne-kilometres to and from China compared with the same time last year. Notably, there was a 51 per cent increase in capacity to and from Central Asian market and a 13 per cent decrease in Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA). However, despite the average decease in traffic to EMEA, there was an upward trend through the period and capacity had recovered to last year’s levels by the end of April.

There has also been a slight shift in the distribution of cargo flights between geographic regions. While flights to and from Central Asia accounted for 15 per cent of all cargo flights in March and April in 2019, they increased to 20 per cent in 2020. In comparison, 35 per cent of the cargo flights were EMEA-bound in 2019, but this dropped to 25 per cent in 2020. The significant increase in cargo capacity flown to Central Asia and simultaneous decrease in the capacity with EMEA may hint that the cargo carriers are flying with heavier loads, but the reduced range requires stopping in Central Asia airports such as Novosibirsk for refuelling before continuing to Europe.

The global reduction in cargo capacity has also resulted in a surge in cargo rates. For example, the cargo rates from China to Europe more than doubled compared with those of last year, according to the freight analysis firm TAC Index.

To compensate for the increased cost of air freight, and to utilise the grounded fleet, passenger aircraft have been transformed into cargo carriers – some temporarily by strapping cargo to passenger seats and some more permanently refitted for cargo-only use. Remarkably, this has even led to a contract for Lufthansa Technik to convert an A380 to a freighter, 13 years after the original A380 freighter programme was shelved.

The good times for cargo airlines may be winding down though. With Chinese passenger flights starting to recover, domestic cargo traffic in China dropped by 20 per cent between March and April. At their peak, domestic cargo flights in China were 80 per cent above last year’s level at the end of March, declined to 20 per cent in April.