ICF manager Nishaan Rama and analyst Dhruva Kemp argue that airlines prepared to use fifth-freedom agreements as they reconsider their networks in the wake of Covid-19 may well find they have a strong advantage

The impact of Covid-19 continues to have far-reaching consequences for the aviation industry, with IATA predicting airlines will lose $84 billion as passenger demand falls 55 per cent in 2020 as governments around the world introduced sweeping travel restrictions.

Now, with restrictions being gradually eased, it is vital airlines adapt to serve recovering travel demand.

Consumer sentiment in the new world is going to be notably different, with ICF Next’s survey of frequent flyers indicating only 24 per cent expect to travel internationally in 2020.

Therefore it is imperative airlines shape their route networks where possible to anticipated low levels of demand in the coming months, potentially putting the viability of certain routes at risk.

Airlines can take various measures to sustain demand, including reducing frequencies or switching to an alternative aircraft type where possible.

Fifth freedom

Another option could be taking advantage of fifth-freedom agreements and operating multi-stop flights to benefit from demand at an intermediate point on the route in order to supplement weaker point-to-point load factors.

The fifth freedom is defined as the right to fly passengers and cargo between two foreign states, as long as the origin or the final destination of such flights is the registration state of the airline.

Fifth-freedom routes are generally a minority of an airline’s capacity but help gain market share and connect routes that cannot be operated due to limited point-to-point demand or aircraft range restrictions.

As far back as 2016 it was argued that ultra-long-haul services may benefit from lower unit costs by adding a stop to overcome passenger or cargo payload restrictions and reduce the inefficiencies that may cause a higher cost per available seat kilometres (CASK), partly due to a less dense configuration.

The operation of these routes requires appropriate air service agreements, schedule adjustments and slack time for schedule coordination.

In addition, in the post-Covid-19 world, a suitable easing of lockdown restrictions as well as health screening at the intermediate destination will be required for passenger travel.

Singapore’s transatlantic connection

Singapore Airlines has been successful in operating fifth-freedom flights connecting Southeast Asia to the US. Due to aircraft range and payload restrictions it connects to the Americas with a stop in Europe.

There are no direct services between Singapore and Houston and connecting services prior to Singapore Airlines’ service included multiple carriers via Northeast Asia and the Middle East.

There were also no direct flights between Manchester and Houston, with the majority of passengers connecting through Heathrow Airport in London on British Airways and United Airlines.

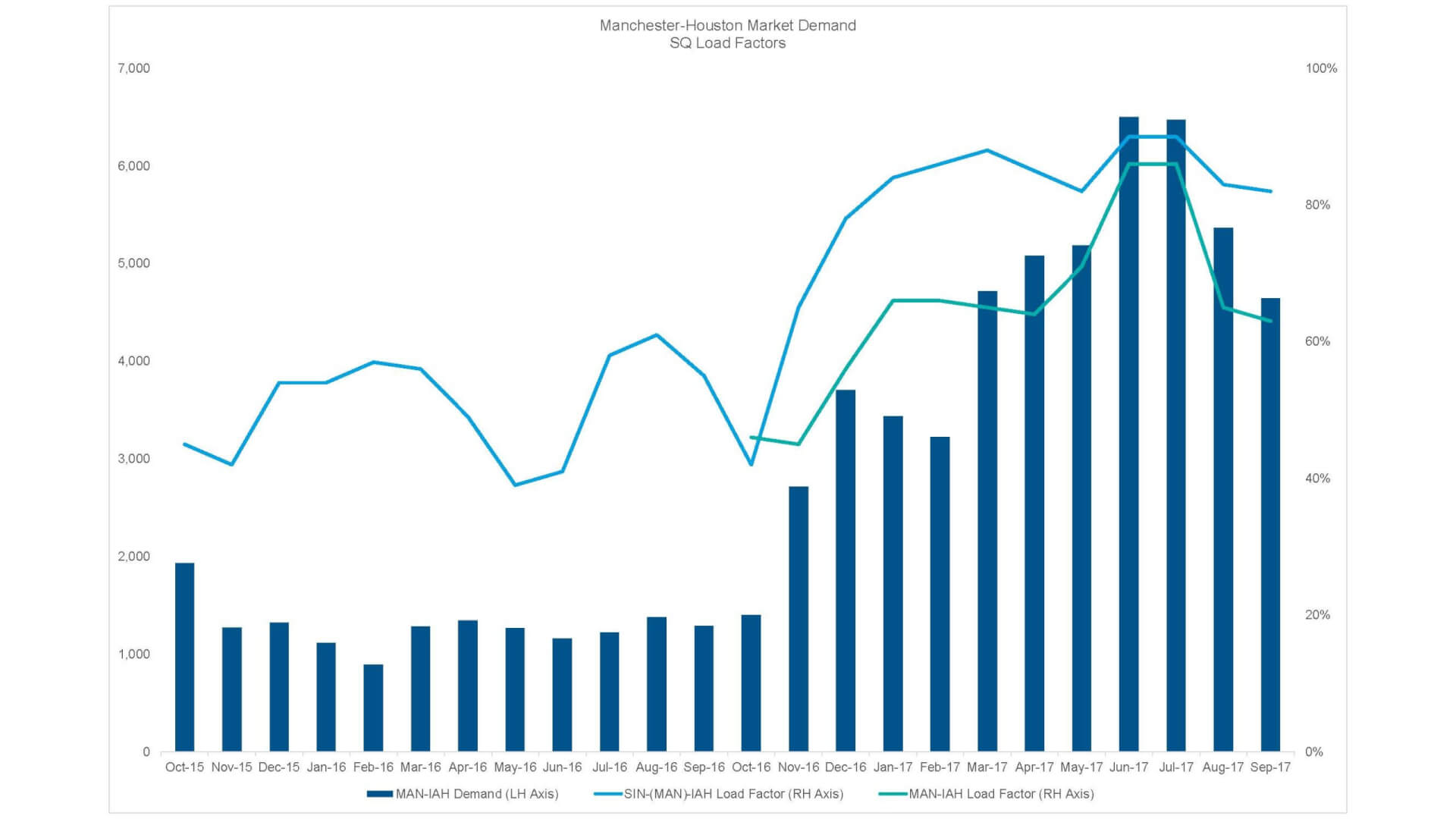

Load factors on Singapore’s Manchester-Houston segment have averaged in the mid-60 per cent since the service started in October 2016, below the load factor it generated on the entire itinerary. The fifth-freedom segment, Manchester-Houston, has, however, stimulated the local market as no direct service had previously existed.

Singapore Airlines’ non-stop connection to Houston further enhances Manchester’s transatlantic connectivity and provides Singapore Airlines services to the US that bypass competition from busier London airports.

Due to falling demand from the pandemic, in May 2020 United applied to reinstate the previously cancelled fifth-freedom Singapore-Hong Kong segment of its San Franciso-Singapore itinerary. The airline will initially operate cargo-only services, but keeping the option to commence passenger services highlights its need to optimise passenger loads in a low-demand environment.

A more connected Africa

African carriers faced issues before the pandemic, including high debt burdens and lower load factors than carriers in other regions while the service reductions have had a considerable impact on many of their already precarious finances.

This may lead to permanent route cancelations or carriers entering administration, as happened with South African Airways, for which a restructuring plan was recently approved, while Air Mauritius entered voluntary administration in April 2020.

Africa’s aviation market is less developed than other regions with demand concentrated in a limited number of airports. In 2019 the top 10 busiest airports in Africa accounted for 47 per cent of total capacity, the second-highest market concentration of all global regions.

Just over a third of airline capacity in Africa is on routes served by only one carrier in 2019, the highest of all regions, driven by a relatively higher share of single-carrier intra-regional and inter-regional services.

Given the relatively concentrated market carriers operate in, route cancellations can lead to a loss of or significantly reduced connections with limited alternatives available.

Ethiopian Airlines exemplifies the connectivity gains available from fifth-freedom routes and has one of the widest global fifth-freedom networks, originating from its base in Addis Ababa.

Its fifth-freedom network includes intra-regional Africa, essentially acting as a regional carrier for the continent. The airline also has fifth-freedom segments between large cities in East Asia. Ethiopian also serves three destinations in the US, New York (JFK), Newark and Houston. The latter two operate via Lomé airport in Togo as a hub for ASKY Airlines, a regional carrier part owned by Ethiopian which allows it to optimise feeder services for its transatlantic services. Newark and Houston are also hubs for United, a codeshare partner for Ethiopian.

Kenya Airways has a fifth-freedom network with a greater emphasis on intra-Africa travel and, similarly to Ethiopian, operates effectively as a regional carrier on these routes.

Both Ethiopian Airlines and Kenya Airways operate fifth-freedom segments within Africa where they are the only carrier on the route, highlighting the connectivity gains for otherwise unserved routes.

Now, as airlines employ a range of strategies as they rebuild their networks and lockdowns are lifted, we can see how making use of fifth-freedom rights can boost connectivity while allowing airlines to consolidate their networks. Additionally, it also provides a new load point for belly-hold cargo carriage.

Fifth-freedom flights may also prove to be more dynamic when coupled with a codeshare agreement since another airline will be able to sell tickets to the onward destination aside from just the operating airline.

As airlines begin to recover, there is more need than ever for optimised routing in a low-demand environment.

European renaissance

In late March and early April this year, at the height of the pandemic in Europe, flights in Eurocontrol airspace were down approximately 90 per cent compared to 2019.

Many secondary and regional airports saw all commercial flying end while services that continued to run were largely focused on repatriating international travellers.

Capacity recovery has been piecemeal and has predominantly depended on how lockdowns and travel restrictions have been pared back, which defines where flights can return.

Carriers have since begun reintroducing services and in mid-July flights were down 60 per cent compared to 2019, an improvement on the situation a few months previously.

Secondary and regional airports often have a more limited range of carriers and destinations than larger airports and may rely on feeding hub airports.

As carriers implement new network plans,

these airports have less potential backfill opportunity if an incumbent airline reduces or ceases services.

EasyJet has announced it will close bases at three UK airports, Stansted, Newcastle and Southend, and expects to serve them from away-based aircraft instead. The airline is yet to announce definitive capacity plans and has not indicated it is permanently cutting any routes from the airports.

Closing bases has the potential to reduce frequencies at an airport as it is no longer served by based aircraft.

In 2019, easyJet accounted for 10 per cent of capacity at Stansted, 20 per cent at Newcastle and 47 per cent at Southend, where it is the airport’s largest carrier. Much of its network at the three airports is unique, with 33 per cent, 53 per cent and 33 per cent respectively to destinations only served by the airline.

This is important as should the carrier decide to reduce services, there is potential for back-filling from other carriers if they want to add additional capacity on those routes.

Demand is not the only factor that can lead to reduced air connectivity and domestic recovery is further compounded by stipulations applied to government support packages for environmental reasons.

For example, as part of Air France’s loan from the French government, it will cease domestic services where the same journey by train takes less than two-and-a-half hours. It is reported this limitation will also apply to other carriers to avoid backfilling on the routes.

Similarly, in Austria, Austrian Airlines will cease services on domestic routes with a rail alternative taking less than three hours.

ICF forecasts it will take between five and six years for European traffic to reach pre-Covid-19 levels. For secondary and regional airports to weather this period and show resilience, it is key to continue open discussions with airlines to minimise any potential reduction in capacity and to make use of government financial support schemes for staff and business operations where possible.